The £50 note is getting a makeover. Our largest denomination will be reprinted on the glossy, washing-machine-resistant polymer used for £5 and £10. It’s also getting a brand new figurehead, a new face to gaze thoughtfully up at us from our wallets. And by ‘our’, I mean ‘them’. Other people. The kind usually found with a non-accidental supply of £50 notes, a small, pure-breed dog, and a lavishly-dressed entourage.

Presiding over the picking, and subsequent immortalisation of this to-be-determined character, is the appropriately named ‘Banknote Character Advisory Committee’. The committee has already decided this person will be someone who contributed to the UK’s scientific achievements. Someone who has, to quote the bank’s website, “shaped thought, innovation, leadership or values in the UK” and has “inspired people, not divided them”.

Interestingly, the Committee has taken the bold decision to turn the traditionally behind-closed-doors selection procedure into something a little more fun. They’re allowing the British public, of Boaty Mcboatface fame, to nominate who they’d like to see canonised in the bill’s new design. Sensibly, the committee has imposed some restrictions on the public’s input. For one thing, this is a license to nominate. It’s not an open public vote. Also, in addition to being a scientist, the Committee is only accepting suggestions for real people (so no Notey Mcnoteyface), and in accordance with British law, for people that are deceased (the reigning monarch is the only living person allowed to be portrayed on legal tender).

You might think this would make the British public a little more restrained. But no. Out of the 170,000 or so nominations received by the committee so far, around one third have had to be chucked out because they didn’t meet these basic criteria. Beyond more sensible suggestions, the committee has revealed it has received nominations for Obi Wan Kenobi, Mancunian rascal Liam Gallagher and a unicorn-straddling Harry Maguire.

Fortunately, even with these restrictions, the committee has a great many eligible nominations to choose from. Iconic cosmologist and author Stephen Hawking has emerged as an early frontrunner. Ada Lovelace and Dorothy Hodgkin are also popular choices. And apparently former PM Margaret Thatcher, a practicing chemist before she entered the political world, is also in the running. Unsurprisingly, her candidacy is being both supported and attacked by opposing petitions.

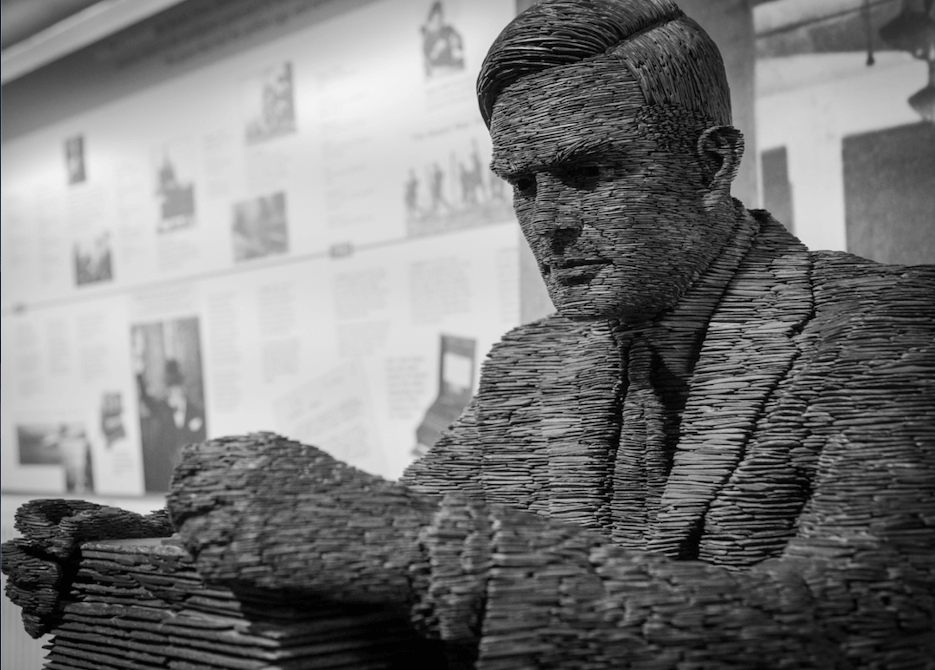

While there are many deserving candidates, we believe Alan Turing should be commemorated on the £50 note.

Our vote: Alan Turing

Turing was a British hero, a mathematical genius, and one of the most influential figures in the development of modern computing. To justify Turing’s candidacy, we have to start with his well-documented work at Bletchley Park during World War II. Turing was instrumental in our breaking of Germany’s Enigma codes, which the Nazis used to encrypt and share vital military information. The intercepting and decoding of these messages gave the Allies a decisive upper hand. So much so that some historians estimate Turing’s work shortened the war by as much as three years, saving more than 20 million lives. And Churchill himself commented that Turing had made the biggest single contribution to the Allies’ victory.

Turing is best known for his work during the war, magnificently (if inaccurately) depicted in the Imitation Game. But he’s less known for his work before and after the war, where he made a series of breakthrough observations in the world of theoretical mathematics. These insights were hugely important to the development of computer science.

In the 1930s he conceived a hypothetical device called the a-machine (later renamed the Turing machine), that would process inputs via a pre-set algorithm – held in some kind of stored memory – to produce outputs. If X is entered, do Y. If Y, then Z. And so on. Thus, he had created a conceptual device that could perform rudimentary computations.

He then devised the Universal Turing Machine, a device capable of emulating all the capabilities of individual Turing Machines. Turing Machines had to be specifically preset with certain algorithmic functions, limiting their computational range. Think of a Turing Machine as a specific piece of software. It can only do certain things, deliver certain outputs, based on its fixed programming. A Universal Turing Machine was more like a modern computer, hosting a variety of applications (or algorithmic settings), and therefore could process any algorithmic function. This was the first example of ‘universal computing’.

After the war, Turing built a number of physical computational systems, most notably the Manchester Mark 1 at Manchester University, which was the world’s fastest computer at the time. It was also one of the first stored-programme computers, joining the likes of the National Physical Laboratory’s (NPL) Pilot ACE, which Turing also helped design. Stored-programme computers retain their programming instructions in electronic memory, making them the direct ancestors of modern computers.

Despite his many computational achievements, Turing is perhaps best known for two things: his work during the war, and his life’s heinous final chapter. In 1952, he was discovered to be having a romantic relationship with Arnold Murray. This was at a time when homosexuality was illegal in the UK. Just by having a relationship with another man, Turing was committing a crime.

Turing appeared in court and admitted to his and Murray’s relationship. He was found guilty of “acts of gross indecency” – the cruel legal terminology ascribed to acts of homosexual and bisexual love. His sentence was chemical castration, a mandatory course of ‘anaphrodisiac’ drugs, designed to repress sexual feelings. Two years later, aged just 41, Turing committed suicide by eating a poisoned apple.

Astonishingly, it wasn’t until 2013 – some 46 years after the decriminalisation of homosexuality – that Turing, a British hero, received a royal pardon. And it wasn’t until three years after that that a law was passed to posthumously pardon all homosexual and bisexual men convicted of subsequently abolished sexual offences. It was appropriately named ‘The Turing Law’.

Turing was brutally mistreated by the country he helped save. Nothing can ever make up for that. Still, we must make an effort to acknowledge the crimes of our past and seek atonement for the subjugation, oppression and marginalisation of millions LGTBQ+ people. In that pursuit, we must also look to grant recognition and appreciation to all persons who’ve been so contemptibly deprived of it.

On their own, Turing’s achievements in the fields of cryptography and computer science more than qualify him for immortalisation on the new £50 note. But choosing him would be more than a salute to his genius and lasting influence. Honouring Turing would be a celebration of our most precious ideals of love and human equality, and a reaffirmation of the progress we have made, and must still yet make.

For these reasons, and many more besides, we support Turing’s immortalisation on the £50 note.